Revisiting Good Old-Fashioned Artificial Intelligence (GOFAI)

In Defense of Bounded, Non-Machine Learning AI

When we talk about "Artificial Intelligence" (AI) today, we still refer to a blurry, loosely defined cluster of techniques that our computers can perform. Whether it's detecting where a face is in an image (and/or whose face it is), or attempting to summarize a paper (perhaps in a conversational way), we refer to these things as "AI."

While there have been endless attempts to define AI (from books to papers to blog posts), this essay won't do that. In fact, it's in my opinion that it's not entirely possible to create a well-defined and all-encompassing definition of "AI," and it's not actually very fruitful to do that. But that's a discussion for a different time.

Instead, I want to sit with the fact that just about all AI systems we talk about and engage with today are rooted in Machine Learning (ML), a subset of AI that applies statistical algorithms to data in order to perform tasks. In the example of detecting a face in an image, whereas one AI approach is to track all the different components of a face (eyes, nose, mouth, etc.) and try to identify if the particular arrangement of pixels in an image map onto the template of a face, another AI approach is to take millions of examples of faces, extract the general features these example faces have, and then find correlations of these features represented in future, unseen images. Whereas the first example tries to make use of specific predefined rules or knowledge, the second example is one of Machine Learning, where the computer is accomplishing a task by using correlation to past data.

In some ways, it's a lot easier to define Machine Learning, which does have a specific set of techniques associated with it (for the most part). As I've mentioned before, these are systems that make use of data to build statistical models about the world. All of "Generative AI" uses Machine Learning — and a vast amount of (often stolen) data at that! In some ways, we've largely forgotten what non-Machine Learning AI even looks like, and that's, in a lot of ways, intentional.

. . .

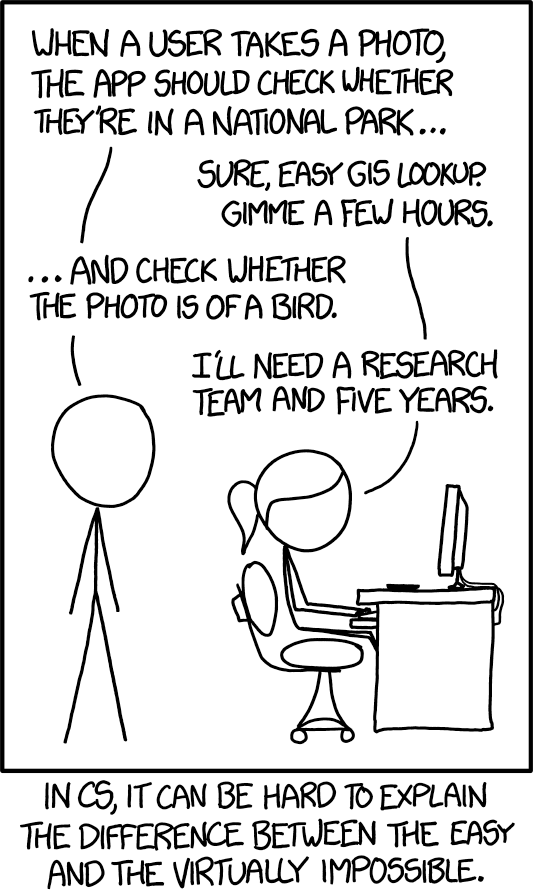

Starting in the 2010's, we started to hear the idea that "data is the new oil" or "currency" or "gold" or whatever economy-driving object you want to think about. In a large part, this was because data — once processed through a Machine Learning system — was becoming tremendously and increasingly useful for helping computers automate tasks that were previously thought to be impossible. There was a joke from September 2014 by xkcd that whereas checking whether a digital photo was taken in a national park is a relatively easy task to do, checking whether the photo was of a bird is still a difficult research problem. This comic actually motivated the image hosting company Flickr to develop a (somewhat joke) application called PARK or BIRD that used Machine Learning in the form of a "deep convolutional neural network" to solve the challenge.

Flickr released this application only a month after the original xkcd comic in October 2014, showing that the task wasn't as hard as it seemed. This was in a large part because of some tremendous advances in three things: (1) the statistical machine learning algorithms we had, (2) the computational capabilities of our available hardware, and (3) the sheer amount of data we now had access to. It's no coincidence that the group that was able to most readily solve the BIRD challenge was an image hosting company, one with access to millions of images at their disposal.

This story is still very much true today with Generative AI. We're in a moment where AI is driving a global hardware shortage, and has been for the past few years. We're in a moment where generative AI companies scanned and destroyed millions of books in order to get enough data to train their statistical models. And all of this for the sake of Machine Learning... to do what, exactly?

. . .

When I was an educator in the late 2010's, developing some of the earliest curriculum for teaching Artificial Intelligence to high schoolers, students and teachers often asked me, "Well, what is an example of Artificial Intelligence that isn't Machine Learning?"

The bulk of concepts and techniques that are taught today are within the realm of Machine Learning, where we use tremendous amounts of data to "train" a statistical model so that it can do that task of summarizing a paper or "generating" a fake image of a politician or loved one. With this Machine Learning approach to pursuing Artificial Intelligence, you fundamentally need a lot of data and a lot of processing power (like in the form of a heavily-polluting data center that's irreversibly harming the environment and the health of Black communities). But it wasn't always this way with Artificial Intelligence.

Even before this tremendous boom in data hungry Machine Learning systems, epitomized today by Generative AI, we had AI systems that could do fairly well at complex tasks. Route-finding (such as with early Google Maps or even MapQuest) existed long before the 2010's, and it wasn't like every time you asked for directions, a human literally mapped out that specific route for you. No, we made use of traditional search algorithms that helped you get from point A to point B. In fact, search algorithms were so effective, that we could apply them to the space of decisions; that is, given a sequential series of decisions to make, what would be the most optimal decision path to take to get to a desired outcome? This was but one framing used by AI systems that served as an alternate (and today, a complement) to Machine Learning. This includes famous algorithms such as A* that can be used for so many problems, from optimal routing on a map to playing Super Mario at an above-human level. Search algorithms without Machine Learning proved to be so effective that they were what allowed the AI system Deep Blue to defeat grandmaster Gary Kasparov in chess in 1997 — long before we turned to data to solve all of our problems.

. . .

Artificial Intelligence, and even Machine Learning, are not new. They have been theorized for generations, with conceptual roots going back to (pre-)biblical times with humans hypothesizing about the creation of creatures just as smart as we are (see also: the golem). We've had long histories of thinking about thinking, or what makes us intelligent, whether that's to better understand ourselves (and the belief that we occupy a privileged position in the universe) or to understand how we can create automated things like ourselves. When Alan Turing proposed his famous Turing Test, or whether you could deceive a human into thinking that a computer was another human, the idea of replicating intelligence in non-human entities was already heavily worked upon. From philosophizing if we could identify thinking and feeling by observing the inner workings of a mill, to engineering a fake automaton chess player called the Mechanical Turk, we've been fixated on the ideas and constructions of intelligence, thinking, computation, etc. for a long time before "computers" as we know them today.

Today's Machine Learning — whose techniques power Generative AI — has roots back to the mid-1900's, with concepts such as the "artificial neural network" or Rosenblatt's "perceptron" from 1958. Inspired by the neurons of the human mind (though not at all accurate of how we today understand the brain to work), there was a belief that you could build a system to complete a task by reweighting the connections between neurons, allowing them to effectively learn over time. To make a very long story short, this model of Artificial Intelligence is what has won out today, in the form of "deep learning" (or having multiple layers of perceptrons/neurons connected to one another) and extremely complex systems of neural networks (such as the "deep convolutional neural network") that together create a statistical model when fed extraordinary amounts of data. But it took a long time to get here, namely because of limitations with computational power and availability of data that we just simply didn't have until the 2010's. In the interim, research pursued many other avenues to achieve Artificial Intelligence that simply weren't in this vein of Machine Learning.

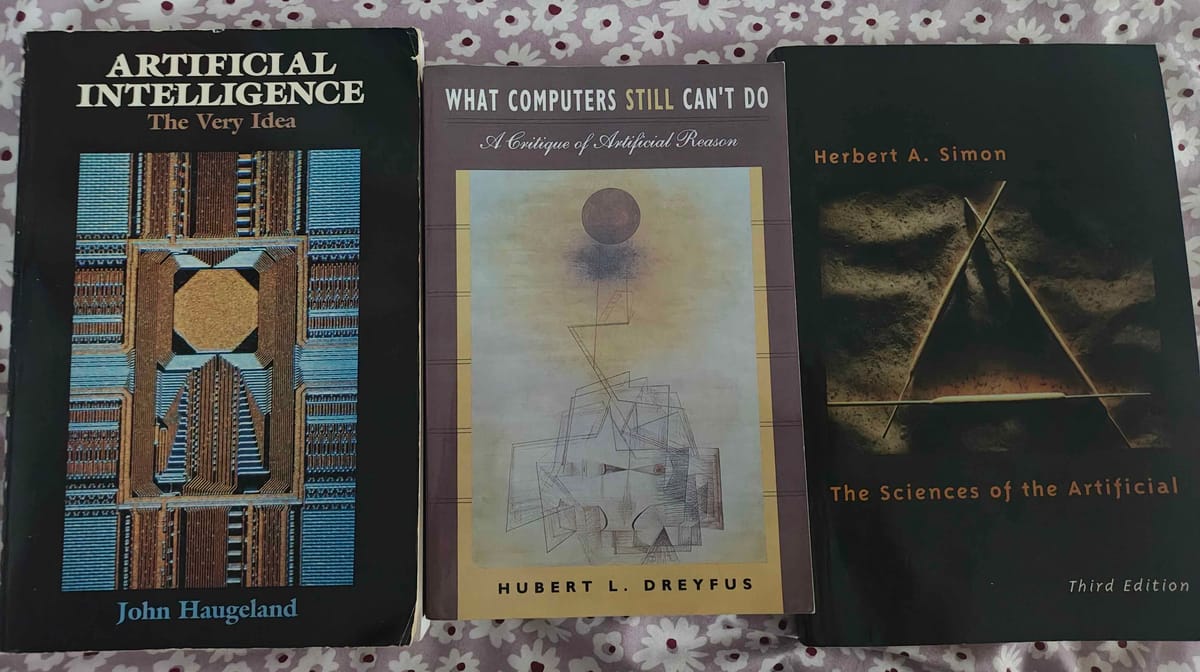

In the 1985 book Artificial Intelligence, John Haugeland defines the term "Good Old-Fashioned Artificial Intelligence," or GOFAI, to refer to an approach to AI that centers the manipulation of symbols. He originally conceives of GOFAI as a branch of cognitive science that's rooted in the Hobbesian conception of computation, but much of these philosophical roots in the term are forgotten (or ignored) today. We roughly associate GOFAI with what is now referred to as "symbolic AI," which includes other terms such as "expert systems," "knowledge-based systems," or "rule-based systems" that once held far more meaning when pursuing the study and engineering of Artificial Intelligence. For Haugeland, the "success" of GOFAI in replicating human-level intelligence relied on whether the world existed purely as symbols that could be manipulated to allow for reasoning (note for the pedant: in his original conception of the term, he emphasizes that the world needs to be symbols rather than the ability for the world to be represented as symbols). These GOFAI systems operated off the assumption that you could solve a task using logical deduction (e.g., if A, then B), which (spoiler alert!) turned out to be less fruitful than expected.

One of the clear problems with GOFAI is the qualification problem, or needing to list out every possible situation or condition, in order to complete a task. Returning to the example of identifying a face in an image, there's just simply no way to list out all the possible arrangements of pixels that gives you a human face, especially given that faces look dramatically different (and not everyone's faces have two eyes, a nose, and a mouth). Indeed, it's quite bad at the task of facial recognition. So GOFAI was seen as a failed branch of AI. But failure here is not in the sense that it couldn't complete a specific task — it's actually pretty good at very specific things — but rather that it couldn't complete any task. Or, restated for clarity, GOFAI was seen as a failure because it couldn't solve any general problem.

Even in the late-1900's, researchers were obsessed with the pursuit of an Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), though presented in different terms. In the 1969 book The Science of the Artificial, Herbert Simon proposed the existence of a General Problem Solver (GPS), to which he later theorized in 1976 with Allen Newell, that GOFAI could achieve. It is in this context that John Haugeland introduces the concept of GOFAI, in asking whether it is indeed sufficient for achieving general intelligence. Even here, we see how the questions of computation, problem-solving, and generalizability have been entangled, guiding the research agendas in Artificial Intelligence to come. And as Timnit Gebru and Emile Torres have argued, this pursuit of Artificial General Intelligence has become an obsession of what they call the TESCREAL Bundle, a collection of ideologies that's rooted in eugenics, control, and power.

. . .

But what if enough is enough? What if all we need is the route-finding abilities of ProQuest or the game-playing prowess of DeepBlue? What if we don't want to pollute the environment, or steal the labor of artists, or cause a global shortage in hardware (which itself requires tremendous, invisibilized human labor and environmental damage to create)? In this essay, I present alternative forms of AI that do not use Machine Learning, including GOFAI and search algorithms. Traditional "Reinforcement Learning" also does not need the opulence of data that we take for granted today (literally, these companies are taking the data gratis, or through theft today). Though the original term GOFAI specifically refers to symbolic AI and holds with it the connotation of a "failed" tradition of AI research, I revisit it in this essay to implore us to rethink what "failure" means and whether that "failure" means it is undesirable or insufficient for our needs.

In many ways, it is the fervent (and often irresponsible) pursuit of Artificial General Intelligence that is undesirable, in terms of society's well-being and environmental protection. It is because we keep trying to create systems that can solve tasks generally (which is something that Generative AI in the form of "foundation" or "frontier" models allege to be able to do) that we sacrifice research into and use of systems that are "good enough" at specific tasks. In fact, this sacrifice has led to the reality that these generalized models are incapable of doing old, solved tasks — such as in the example of ChatGPT being unable to even count to 100. These Generative AI models (also referred to as "stochastic parrots") have so thoroughly dominated the imaginary of AI researchers that we forget alternatives exist. In this essay, I move us to imagine differently, by drawing on the historical example of GOFAI as a counter to the dominant Machine Learning-based AI that we see today. In some ways, I'm possibly arguing that we should expand the definition of "Good Old-Fashioned Artificial Intelligence" (GOFAI) such that it refers to any type of AI that doesn't use data to train a statistical model. And in contrast to Haugeland, it's actually the belief that GOFAI can't and is no longer intended to simulate Artificial General Intelligence that makes it so meaningful. In doing so, I hope to provide an alternative to the course we are already on, one that heads us towards further labor exploitation, loss of privacy, environmental destruction, and cult-like eugenic futures...

. . .

To close, I argue that GOFAI has its merits in presenting us with an alternate, non-data-reliant, non-generalizing approach to Artificial Intelligence. Whereas Generative AI today is so deeply entrenched in the need to steal data, and requires massive data centers that pollute our environment to run, I think it's reasonable — if not ethically pertinent — for us to ask what an alternative looks like. I, for one, don't think that all AI is bad, and I write this essay to illustrate that there are examples of AI that follow a very different tradition and approach to solving tasks. When we say "destroy AI," I think we're rightfully talking about about all AI that exists today, as just about all of it is rooted in a Machine Learning paradigm that's particularly harmful to us and the world around us. I think a lot of us are mistaken in our critiques of AI to mean that we "hate" AI entirely or are Luddites in some derogatory way, when really many of us come from AI backgrounds and want something better. I'm here to ask the question, is there something else (a different form of AI) that's still valuable to us and permissible to use?

Of course, what matters at the end of the day is what we're using the AI technologies for. If we develop a GOFAI system that helps with more optimal military operations, I don't think it's any better than Generative AI. Ultimately, I'm arguing that if we want to pursue AI at all, we need to find something that isn't built off exploitation, capitalism, and capture. I'm arguing that the very foundations of Generative AI — rooted in Machine Learning and the pursuit for Artificial General Intelligence — are perhaps ethically compromised to begin with. It's here that I offer the (possibly shocking) assertion: what if the limitations of bounded, GOFAI are an ethical good? What if the constraints of GOFAI should be taken as natural constraints on what we build with AI?

Revisiting the example of identifying faces in images once more, what if it's good that we can't build a system that's effective at recognizing faces (through Machine Learning)? After all, there are all sorts of reasons why facial recognition is always ethically problematic, especially from a surveillance and privacy standpoint. Here, I challenge us to wonder if, by what they can accomplish, the requirement of needing to use large swaths of data is what makes these AI systems so unethical, and we should actually do away with any system that makes use of Machine Learning, as a starting point. Because effective, bounded GOFAI alternatives do already exist, and maybe they're not as bad as the "solution" we've decided to pursue today.